The Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology recently released findings from a study that shed light on threats to Big Sky’s groundwater and identified its direct connection with the Middle Fork of the Gallatin River.

The study, titled “Hydrogeology and Groundwater Availability at Big Sky, Montana” by hydrogeologist James Rose was a product of the bureau’s Ground Water Investigation Program. This program supports science-based water management in Montana by answering site-specific questions that are prioritized and assigned by the Montana Ground Water Steering Committee, as mandated by the Montana Legislature. Projects may be nominated by any individual or group. The Gallatin River Task Force and the Big Sky Water and Sewer District nominated this study as well as a second study that is underway in Gallatin Canyon.

Big Sky relies solely on groundwater for its water supply. Within this reality, we are vulnerable to water shortages given the future with continued community growth and with less snow predicted as a result of climate change.

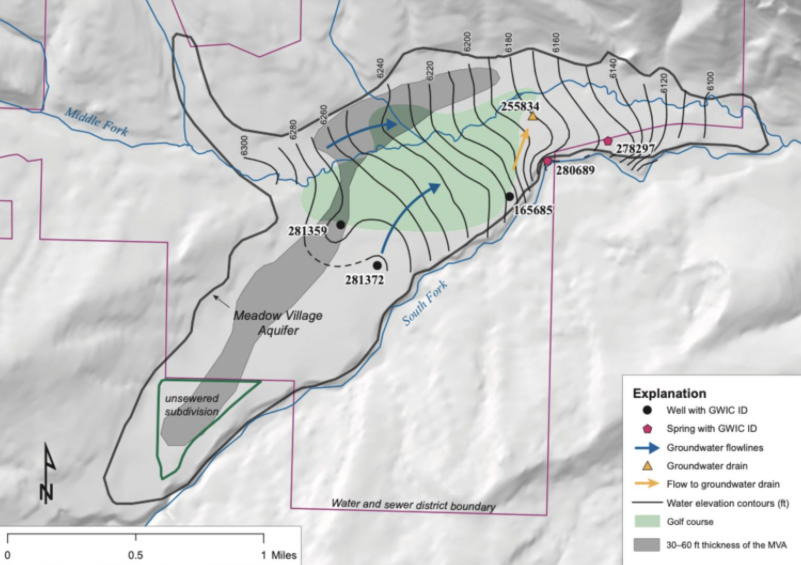

The purpose of the Big Sky study was to define the geology of Big Sky’s aquifers and characterize the water quality so that local and state entities could evaluate the effects of future water development. The study area covered the Mountain and Meadow Village areas, with a specific focus on the Meadow Village Aquifer, the main drinking water source for the Meadow area. Groundwater and surface-water data were collected from 2013 through 2016.

The Gallatin River Task Force asked MBMG hydrogeologist and local resident Mike Richter to consider community questions and key findings related to the study and how to best apply the knowledge gained from the report. What follows are a dozen takeaways from our conversation concerning this technically detailed, scientifically based report. These points address some of the community questions posed during groundwater study presentations hosted by the Gallatin River Task Force on May 17.

1. The Meadow Village Aquifer, or the MVA, is a small but productive aquifer that, according to the study, is “especially vulnerable” to contamination from activities on the land surface, like fertilizer or pesticide application, and over-pumping which has the potential to reduce streamflow in the Middle Fork.

2. Future increases in pumping (groundwater withdrawals) from the MVA are likely to reduce baseflow in the Middle Fork.

3. Groundwater and surface water in the MVA are directly connected. This means that in some places, the Middle Fork feeds the groundwater and in other places, the groundwater feeds the Middle Fork. As the Middle Fork enters Meadow Village, the stream recharges the MVA by adding water to it. Further downstream, the Middle Fork gains water from the MVA, unless the pumping of public drinking water wells intercepts this flow.

4. Snowmelt is the most significant recharge source to the aquifer.

5. Heavy rainfall events can also recharge groundwater. The groundwater’s response to rainfall and the unconfined, shallow nature of the aquifer highlight its vulnerability to contamination from the land surface.

6. Septic system discharges, horse feedlots exposed to precipitation or over-applied fertilizers will infiltrate contaminants into the aquifer over time.

7. Contamination of the streams that recharge the aquifer can also potentially contaminate the aquifer due to their connection.

8. In the MVA, groundwater flows northeast, generally parallel to, not toward, the South Fork of the Middle Fork of the Gallatin River, as was previously assumed. On the southeastern edge of the MVA, groundwater with elevated nitrate spills over the top of the shale, as evidenced by springs flowing into the South Fork in the Kircher Park area.

9. Wells with the highest nitrate concentrations are upgradient of the Big Sky golf course. This finding is significant, as it suggests that fertilizer and effluent applied to the golf course may not be the most significant source of elevated nitrate pollution, as previously thought.

10. The report included a statement by the Montana Department of Environmental Quality that an “unsewered development” (figure 11 map) at the far southeast end of the MVA has a “failing community septic system with reported nitrate discharge exceedances from 2016-2020.”

11. Aquifers outside of the MVA are generally low-yielding and unpredictable because of Big Sky’s complex geology.

12. The report encourages connection to public water supply and wastewater systems at new residential and commercial developments. These systems enhance the capacity for professional management of the limited and vulnerable

water resources.

As community growth increases water demand, the MBMG study will provide a basis to address how a growing community deals with a finite, interconnected water resource. The study gives us the information necessary to identify the nature of this resource and allows for educated solutions moving forward.

The Gallatin River Task Force is focused on taking the information therein and developing informed paths forward with community and regional partners for addressing our water quantity and quality challenges growth continues. A follow-up in next month’s Every Drop Counts column will focus on the implications of the study, and what those next steps in a strategic process forward will look like.

The full report and other MBMG resources are available in the links below: